Written by Fred Magdoff and first published at Monthly Review

Two weeks ago I returned from my fiftieth class reunion at Oberlin College in Ohio. The brief discussions I had there with environmental faculty and students left me feeling a bit dazed. So many good and intelligent people, so concerned, and doing what they think and hope will help heal the environment—this college has one of the best environmental education programs in the country.

However, I was left disappointed and profoundly discouraged by the lack of discussion—or even interest in having a real continuing discussion and debate—regarding the root causes of our environmental disasters. Not just climate change, but also pollution of the air, water, soil, and living organisms, the loss of biodiversity both aboveground and in the soil, the extinction of species, and the overuse and misuse of both renewable and nonrenewable natural resources.

It is as though there is a flat tire with perhaps a thousand holes and people are working on the best way to patch this hole or that one. No one there seems to consider that the problem might be the tire itself—that the design and materials utilized are not appropriate to the way it is being used. And, if that is the case, then no amount of patching can solve the flat tire problem. It is of the utmost importance to be able to distinguish between symptoms (that most people call “problems” or “crises”) and underlying causes.

I ran into this confusion between symptoms and underlying causes time and time again in agricultural science and farming practices. Soils may be prone to erosion, store little water, grow crops that are susceptible to diseases and insect attack, become compacted, or have low fertility. Farmers (and extension specialists), usually think of and deal with these as individual problems—using pesticide applications, lots of commercial fertilizers, irrigating more frequently, using heavier equipment, and so on. In fact, I spent a significant portion of my career as a soil scientist helping to deal with the negative side effects of one of these responses—excess fertilizer use, especially nitrogen and phosphorus.

(As an aside, as I was preparing this talk, an unbelievable thirty-five tons of nitrogen in the nitrate form, worth approximately $35,000, flowed down the Raccoon River past Des Moines, Iowa, on the way to the Mississippi and the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico. This flushing of nitrate out of the soil by prolonged spring rains, partially the result of nitrate left over after last year’s drought [2012], was mainly a consequence of an ecologically damaging, but profitable, emphasis on growing corn and soybeans without an ecologically sound crop rotation.)

However, what I learned over time was that in reality these are symptoms of an unhealthy soil and a simplified approach to soil and crop management. The same is true of never-ending unemployment, inequality and poverty, the systemic necessity of perpetual growth, and pollution of air, water, soil, and organisms. As harmful as each of these is, they are all only symptoms—of an economic system that is essentially unmanaged. Of course large corporations and politicians that represent them try to manage national and international laws, regulations, and markets in such ways that it becomes easier for them to make more money. But with individual corporations and other private capital making decisions which consider only their own interests, the system as a whole alternates between periods of growth (that nowadays are pretty lackluster) and periods of recession. Addressing individual symptoms alone is not sufficient for the tasks we need to undertake—either to create healthy soils or to create an ecologically based and humane society.

One of the neglected issues regarding thinking and acting about the environment—perhaps the most critical of all—is, to borrow a phrase from the first President Bush, the vision thing. The environmental movement is lacking any kind of meaningful vision as to what a truly ecologically sound and socially just society would look like and how it might operate. I am not talking about a blueprint with all sorts of details, but rather an agreement on essential characteristics of such a system. Without a vision—including some conception of the essential parts of such a system, the chances of actually getting to such a society are essentially zero. Or, as James Baldwin put it in a commonly cited but still very appropriate passage, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” It is my contention that we are not facing the root cause of our problems, and until we do, there is no hope of solving the social and ecological problems confronting the world.

Before going into some suggested characteristics of such a

system—one that is ecologically sound and socially just—it seems as if most

environmentalists think that the answer is to change capitalism. However, none

of the suggested tinkering—with banks, international institutions such as the

IMF or the World Bank, environmental regulations, worker cooperatives, trying

to use markets to reduce pollution, etc.—gets to the heart of the matter. This,

of course, does not mean that we should abandon all attempts to buy more time

and help educate others through involvement in here-and-now activism.

However, the primary problem is the inner moving force of capitalism—its Achilles heel regarding the environment—the unending accumulation of capital, which means perpetual “creative destruction.” Produce and sell more stuff next year and more than that in the following year…for all of eternity.1 In such an economy there can be no concept of “enough.” There cannot be an endpoint to the production and consumption of ever-greater amounts of stuff. No-growth capitalism is an oxymoron.

There are severe repercussions for many people when economic expansion falters—because it is only through growth that capitalism creates jobs for new workers and for those displaced by automation (nowadays by robots and software programs). In the period from 1949 to 2012, unemployment increased in twenty-one years, about one-third of the time. During those twenty-one years the average annual real GDP growth rate was only 0.8 percent. Although the business cycle does not neatly correspond to calendar years, it is apparent that significant real GDP growth, around 2 percent or greater, is needed to hold down the unemployment rate. The U.S. GDP is currently growing at about a 2 percent rate, with relatively sluggish job growth. As of May 2013, there are still 2.3 million fewer people working than before the start of the Great Recession five-and-a-half years ago. And there are approximately 5.6 million fewer people working in full-time jobs.

What is the implication for the environment of this growth imperative of capitalism and the need to have growth in order to create jobs? Almost all environmentalists understand that we need to have an economy that does not grow and is still able to function. But if the economy continues growing at its current anemic rate, the GDP will double in 35 years (see Chart 1). If it were to grow at a more healthy rate, the GDP would double in less than twenty-five years. Although a doubling of the GDP will certainly mean more stuff produced, more resources used and more pollution, it does not mean that they will necessarily double.

Just to give a small and somewhat humorous example of the problem, here is a passage from a 2013 New York Times Magazine section (in an issue devoted to inventions):

Booty Pop, padded underwear that makes a person’s backside look bigger and shapelier, an idea so simple its incredible that it took until 2008 for someone to perfect it…. Two friends…were struck by the popularity of bun-lift surgery and thought there had to be a safer, cheaper way for women to achieve the same effect. So [one of them] glued the padding from her bra into a pair of underpants, found a manufacturer in Asia to produce a version of it that met her specifications; and then introduced it to the world on a cable-television show. They have since sold almost two million Booty Pops.2

A society that allows (not to mention encourages) such a waste of capital, and both human and natural resources, will never be ecologically sound and will never be socially just. It is not an issue, as some have said, of simply changing from a “growth philosophy,” “growth model,” “growth paradigm,” “domination ethic,” or the focus on GDP growth by economists and the media.

Capitalism’s growth imperative has nothing to do with philosophies, models, paradigms, ethics, or which numbers pundits and economists focus on. Neither can it be “reinvented,” as some think, to be ecologically sound and socially just. Rather, it is an economic system that has basic internal forces—especially the profit motive and competition among firms—that operate in such a way as to promote exponential growth while simultaneously causing massive negative social and ecological effects. And when growth in this system fails, what Herman Daly refers to as “a failed growth economy,” the cruelest forms of austerity prevail—giving rise to more and more unequal conditions and more ruthless forms of exploitation of both human beings and the earth.

Occasionally even a major capitalist sees the weaknesses of the system. After mentioning what he thinks are the strong points of capitalism (some of which I would take issue with), Jeremy Grantham, the environmental philanthropist and legendary fund manager, goes on the explain the following: “However, it [capitalism] is totally ill-equipped to deal with a small handful of issues. Unfortunately, today, they are the issues that are absolutely central to our long-term wellbeing and even survival.”3

There are some who think that capitalism should be saved because they are under the mistaken notion that capitalism equals democracy. There are, of course, plenty of examples of dictatorships that were capitalist (in many countries of the South, as well as Spain, Greece, Germany, and Italy). For those under the illusion the United States is a democracy because you can vote every four years for a president (or for members of the House of Representatives every two years and the Senate every six)—choosing between candidates of two parties that are both owned lock, stock, and barrel by corporate interest—I urge you to read a short article by Joseph Stiglitz, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, and for the 1%,” as well as many other sources on the U.S. plutocracy.4

The nationally coordinated shutting down of one of the most promising modern exercises of democratic rights in the United States—the Occupy movement—by simultaneous police raids on the Occupy sites, indicates how little tolerance there is for mass expressions of dissenting views. And now with the scandal accompanying Edward Snowden’s release of National Security Agency documents we can see the extent of U.S. government spying on citizens as well as many abroad—in clear violation of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”5

I have not heard another argument regarding just what it is about the capitalist system that is so good that it should be preserved. It is true that as part of its growth imperative there is constant innovation to find new products to sell or new processes of production. But there is no reason why there can’t be innovation in a non-capitalist system—if not the churning, continual, “creative destruction” type.

Why won’t there be people in an ecologically sound and socially just society who think of better—more environmentally sound ways—of doing something or those engaged in scientific research not for profit but for the love of science, the profound need of some to understand at a deeper level, or just for the benefit of humanity (for example, in the health sciences)? Even today, many people are engaged in innovation for reasons other than the potential monetary payoff.

An ecologically sound and socially just economy can be defined as one that encourages all people to develop their full human potential in such ways that the environment—with all its complexity, essential cycles, and relationships—remains intact, functioning, and healthy. In other words, an economy designed to be at the service of humanity, which includes the environment on which we and other species depend. This is an economy that can stop growing and can function well during a steady state, while meeting the needs of people and the rest of the natural world.

The ideas and suggested characteristics, principles, and procedures below are not a grab bag of possibilities from which one can choose. Rather, the various parts need each other in order for the economy and social system to function in an ecologically sound and socially just way. Each fits into one or more of the five attributes or pillars of strong natural systems: self-regulation; self-sufficiency; diversity and interdependence; efficiency (of cycling of energy and nutrients by closely linked metabolic relations); and resilience through self-renewal.

I have outlined some of the main characteristics that I think are essential for an ecologically and socially humane and just economy and society. These are incompatible—in almost every way—with a capitalist economy. Doing away step by step with capitalism in a necessary long revolution will not automatically bring positive social or ecological change. That change will happen only if a large portion of the population believe in, and fight for, an environmentally sound and socially just society.

And it will take a huge shift in almost all of human activities, ways of thinking and behaving, including how we relate to each other and interact with the environment. New ethics will be needed for this new society to function. This is not an easy task, but what is the alternative? A system that, as it functions normally, destroys the very foundations of life through exploitation, waste, and greed is by definition an antiquated system. This is not an argument in favor of doing nothing in the here-and-now. We should be helping to stop the Keystone XL pipeline and encourage universities and other organizations to divest of holdings in fossil-fuel companies and fight for the environmental rights of poor communities. We can use these struggles in order to help educate others that, to solve the overall ecological crisis in all its ramifications, another system is necessary.

Is this an unattainable “utopia”? I think that, if it ever comes into being, an economy and society that is ecologically sound and socially just will have to embody most of the characteristics I have described above. There is no doubt that it will not happen in the near future. But I contend that it is no more utopian than to think that the financial and other strong business powers and their governmental representatives will allow you to make major changes to the financial system or the way international trade operates. What are the chances of, as some ecological economists have suggested, forcing banks to have very high (some have said 100 percent) reserves so they cannot create significant amount of debt or making major modifications in the workings of the World Bank and rules of the World Trade Organization so that they encourage equality and environmental justice? I think that those ideas are perhaps even more utopian than the possible creation of a new society. As the economist Joan Robinson once explained, “Any government which had both the power and the will to remedy the major defects of the capitalist system would have the will and the power to abolish it altogether.”8

It has been said, accurately in my opinion, that most people in this society can more easily imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. I fear that barbarism may be the fate that awaits our grandchildren and their children unless we can change that way of thinking and start to envision, and begin to work towards, an economy and society under truly democratic social control with the very purpose being to satisfy basic human needs, which as I have stressed many times, includes a healthy and thriving environment.

There are severe repercussions for many people when economic expansion falters—because it is only through growth that capitalism creates jobs for new workers and for those displaced by automation (nowadays by robots and software programs). In the period from 1949 to 2012, unemployment increased in twenty-one years, about one-third of the time. During those twenty-one years the average annual real GDP growth rate was only 0.8 percent. Although the business cycle does not neatly correspond to calendar years, it is apparent that significant real GDP growth, around 2 percent or greater, is needed to hold down the unemployment rate. The U.S. GDP is currently growing at about a 2 percent rate, with relatively sluggish job growth. As of May 2013, there are still 2.3 million fewer people working than before the start of the Great Recession five-and-a-half years ago. And there are approximately 5.6 million fewer people working in full-time jobs.

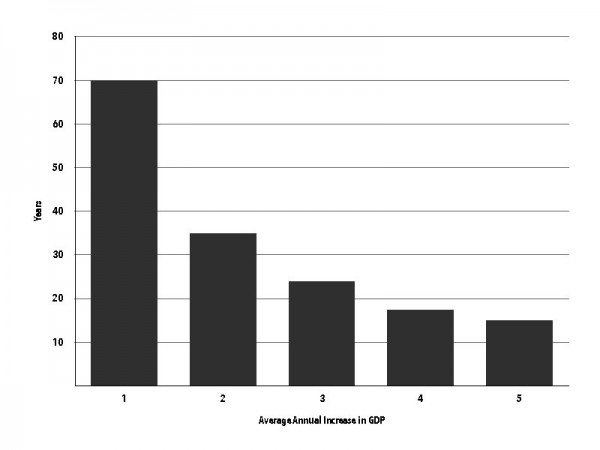

What is the implication for the environment of this growth imperative of capitalism and the need to have growth in order to create jobs? Almost all environmentalists understand that we need to have an economy that does not grow and is still able to function. But if the economy continues growing at its current anemic rate, the GDP will double in 35 years (see Chart 1). If it were to grow at a more healthy rate, the GDP would double in less than twenty-five years. Although a doubling of the GDP will certainly mean more stuff produced, more resources used and more pollution, it does not mean that they will necessarily double.

Chart 1. Years to Doubling of GDP at Different GDP Growth Rates

Source: Calculated by author.

Booty Pop, padded underwear that makes a person’s backside look bigger and shapelier, an idea so simple its incredible that it took until 2008 for someone to perfect it…. Two friends…were struck by the popularity of bun-lift surgery and thought there had to be a safer, cheaper way for women to achieve the same effect. So [one of them] glued the padding from her bra into a pair of underpants, found a manufacturer in Asia to produce a version of it that met her specifications; and then introduced it to the world on a cable-television show. They have since sold almost two million Booty Pops.2

A society that allows (not to mention encourages) such a waste of capital, and both human and natural resources, will never be ecologically sound and will never be socially just. It is not an issue, as some have said, of simply changing from a “growth philosophy,” “growth model,” “growth paradigm,” “domination ethic,” or the focus on GDP growth by economists and the media.

Capitalism’s growth imperative has nothing to do with philosophies, models, paradigms, ethics, or which numbers pundits and economists focus on. Neither can it be “reinvented,” as some think, to be ecologically sound and socially just. Rather, it is an economic system that has basic internal forces—especially the profit motive and competition among firms—that operate in such a way as to promote exponential growth while simultaneously causing massive negative social and ecological effects. And when growth in this system fails, what Herman Daly refers to as “a failed growth economy,” the cruelest forms of austerity prevail—giving rise to more and more unequal conditions and more ruthless forms of exploitation of both human beings and the earth.

Occasionally even a major capitalist sees the weaknesses of the system. After mentioning what he thinks are the strong points of capitalism (some of which I would take issue with), Jeremy Grantham, the environmental philanthropist and legendary fund manager, goes on the explain the following: “However, it [capitalism] is totally ill-equipped to deal with a small handful of issues. Unfortunately, today, they are the issues that are absolutely central to our long-term wellbeing and even survival.”3

There are some who think that capitalism should be saved because they are under the mistaken notion that capitalism equals democracy. There are, of course, plenty of examples of dictatorships that were capitalist (in many countries of the South, as well as Spain, Greece, Germany, and Italy). For those under the illusion the United States is a democracy because you can vote every four years for a president (or for members of the House of Representatives every two years and the Senate every six)—choosing between candidates of two parties that are both owned lock, stock, and barrel by corporate interest—I urge you to read a short article by Joseph Stiglitz, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, and for the 1%,” as well as many other sources on the U.S. plutocracy.4

The nationally coordinated shutting down of one of the most promising modern exercises of democratic rights in the United States—the Occupy movement—by simultaneous police raids on the Occupy sites, indicates how little tolerance there is for mass expressions of dissenting views. And now with the scandal accompanying Edward Snowden’s release of National Security Agency documents we can see the extent of U.S. government spying on citizens as well as many abroad—in clear violation of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”5

I have not heard another argument regarding just what it is about the capitalist system that is so good that it should be preserved. It is true that as part of its growth imperative there is constant innovation to find new products to sell or new processes of production. But there is no reason why there can’t be innovation in a non-capitalist system—if not the churning, continual, “creative destruction” type.

Why won’t there be people in an ecologically sound and socially just society who think of better—more environmentally sound ways—of doing something or those engaged in scientific research not for profit but for the love of science, the profound need of some to understand at a deeper level, or just for the benefit of humanity (for example, in the health sciences)? Even today, many people are engaged in innovation for reasons other than the potential monetary payoff.

An ecologically sound and socially just economy can be defined as one that encourages all people to develop their full human potential in such ways that the environment—with all its complexity, essential cycles, and relationships—remains intact, functioning, and healthy. In other words, an economy designed to be at the service of humanity, which includes the environment on which we and other species depend. This is an economy that can stop growing and can function well during a steady state, while meeting the needs of people and the rest of the natural world.

The ideas and suggested characteristics, principles, and procedures below are not a grab bag of possibilities from which one can choose. Rather, the various parts need each other in order for the economy and social system to function in an ecologically sound and socially just way. Each fits into one or more of the five attributes or pillars of strong natural systems: self-regulation; self-sufficiency; diversity and interdependence; efficiency (of cycling of energy and nutrients by closely linked metabolic relations); and resilience through self-renewal.

Social, Economic, and Ecological Principles

- Economic decisions—what to invest in, and what, how, and where to build/produce—are made democratically and for the purpose of fulfilling the basic needs of people. One of the basic needs, of course, is a healthy local, regional, and global environment. Such a society will be oriented to encourage everyone to strive to reach their full human potential. All people can live a culturally and socially rich life, though with a modest amount of stuff—below what is considered necessary for a “middle-class western standard of living.” Note the contrast—production to fulfill human needs versus capitalist production for the purpose of sale in a market in order to generate a profit.

- Workplaces (including farms) will be controlled and managed by the workers and communities in which they are based. There will be no economic exploitation by one person of another and community members will have input into production in their own backyards.

- Once socially determined basic human needs (material and non-material) are met—and after defining how much is enough—the economy stops growing with only neutral or positive side effects for society.

- All people who can work will have a role in the economy. It is important for individuals to feel a part of the community and society and work provides one of those links. If everything is provided for a decent and full existence there is a responsibility for all who are able to participate in providing goods and services.

- Leadership positions (in the economy, community, region, etc.) rotate among the people and there is a system for easy recall of elected officials/leaders.

- Substantive equality among people. This is essential because all will be living at a modest standard in terms of goods and services. In that situation people living at a much higher standard becomes socially unacceptable and unsustainable. People will have richer lives with less stuff because they will have time, assistance, and encouragement to develop and follow their passions—in sports, science, music, dance, writing, painting, handicrafts, or growing flowers—and to more fully engage with family, friends, and community. In a no-growth economy sharing and equality become means to eliminate the remnants of poverty and make sure it does not reappear.

- Interactions between and among communities, regions, and nations will be based on principles of reciprocity, solidarity, and mutual assistance.

- An economy that has a social purpose must involve considerable active management. Planning for short- and longer-term needs begins at the community level (as with the over 30,000 Community Councils of Venezuela) and is intertwined and coordinated with other communities in a regional plan.Once there is social purpose for an economy—as opposed to individuals making decisions that are aimed almost exclusively at obtaining the largest profits possible—there is no way to rationally operate without planning. For example, the production needs for both the First and Second World Wars were accomplished only through planning—and the use of rationing for the public. These plans were essential. After all, given the competition among the military services and with civilian needs as well, how else could you ensure that a particular part, say, a set of ball bearings, got to the right factory at the right time in order to produce an airplane needed for the war effort? It is not possible for markets to do this. In the absence of a planning system for production and distribution, how can we ensure that all people have adequate housing, clean water, sanitation, health services, clothing, and enough food?There may be markets in a post-capitalist society (as there have been since long before the existence of capitalism); in an economy of substantive equality, where basic needs are met, markets may provide some information to planners. When items are scarce, for whatever reason, rationing will ensure that everyone has a fair share—as was done in the United States during the Second World War.(Mostly unacknowledged by economists and pundits, “the market” in capitalist economies is actually a powerful rationing system—rationing according to individual/family resources. Commodities are theoretically available for anyone to purchase—for example, a good new car—but these are out of the reach of people with modest means. And sometimes even basic needs such as food are also beyond the reach of the poor, even in wealthy countries. Close to 50 million people in the United States are considered “food insecure.” This is clearly the result of food rationing occurring in a country that produces bountiful amounts of food.)

Procedures: Ecologically Sound Metabolic Interactions with Nature/Resources

- Each community and region should strive, within reason, to be as self sufficient as possible with respect to basic needs such as water, energy, food, and housing. This is not a call for absolute self-sufficiency but rather for an attempt to build resilient communities and lessen the need for long-distance transport. Clearly not everything is going to be produced in every community, or even every city. But trying to be as self-sufficient as reasonably possible can still be a goal. Redundancy is an important part of both self-sufficiency and resilience. People with similar skills are needed in a community (there cannot just be one electrician) and redundancy in production facilities means that if something happens to one (say a fire), that others can pick up the slack.

- Energy used comes from current (or very recently past) renewable energy sources and used near where it is produced.

- Methods and aims of industrial production and building construction are such that goods have a long life and are easily repaired, repurposed, and/or recycled.

- Non-renewable resources will be conserved and used sparingly and in such ways that they can be recycled efficiently as efforts continue to replace them with renewable ones. Let me give just two examples: one is very well known, and one very new. The first is that legumes can be grown in rotation to supply nitrogen to grain crops (instead of using nitrogen fertilizer produced by using natural gas). The second is a relatively new process in which fungal hyphae replaces Styrofoam as packing or insulating material.6

- Agricultural production will be carried out based on soil and above-ground habitat management that produces healthy plants better able to defend themselves from diseases and insects and to enhance habitat for beneficial organisms. Integrated animal-crop farms will be encouraged—providing a mosaic of habitats—including relatively undisturbed ones. Farm animals will be treated humanely and allowed to do what they would normally want to do and eat what they would normally eat—instead of being confined under cruel conditions and fed corn and soybeans laced with hormones and antibiotics. Farms will rely on legumes for nitrogen for non-legume crops, as well as efficient nutrient cycling for most nutrient needs. Integrated animal-crop farms make this easier to accomplish.7

- Nutrients from human waste (and farm animal waste, as mentioned above), including bodily waste and unused or spoiled food waste, will be cycled back to farmland as efficiently and safely as possible.

- Renewable resources will be used in ways that preserve the resource base and do not create problems for other species/resources. Local communities will cooperatively manage natural resources such as nearby forests and fisheries to perpetuate them for future generations.

- Labor efficiency will not be an important goal (as it is in an economy in which using less labor is a way to enhance profits). For example, ecologically sound and productive agriculture—which will become essential when oil and phosphorus fertilizer run out or become unaffordable to use for agricultural purposes—will take more people working smaller farms with more human and animal labor. These farmers should be able to produce high yields per hectare and per input of energy, but will have lower yields per hour of labor.

- People will be encouraged to live near where they work and use multifaceted and efficient public transportation when needed. Bicycling will be encouraged and private automobiles will play a very small role, if any, in transportation.

- The precautionary principle will be used to evaluate and make decisions on new procedures, production systems, and materials as well as to evaluate any chemicals used by society—to prove safety for humans and the rest of the environment before introduction.

Living in an Ecologically Sound and Socially Just Society

- Communities and regions will develop open and democratic processes to make decisions for infrastructure needs as well other investments. Ways need to be developed for communities and regions to work together in solving problems and sharing resources.

- Education and interactions among people within communities and between communities will strive to encourage those human characteristics and ethics that best fit an ecological and just society.

- People will have sufficient time to develop their various interests. People will work for significantly less than the “eight hour” working day, because so much of what is done now is not socially useful for society at large and would be considered waste in a more rational system. These include luxury cars or yachts, most of the financial system, the intelligence-military-industrial complex (the U.S. military is one of the great destroyers of the environment), the prison-industrial complex, the constant efforts to change fashions and products to induce buying, the sales effort in all its ramifications, and so on. Socially useless, even harmful, products and programs constitute a very large portion of the U.S. economy and utilize as large a share of workers—perhaps as great as half of the labor force and at least as much of the raw materials used.We are all capable of exhibiting a large range of characteristics, from the most brutal to the most altruistic. There is no such thing as an abstract “human nature” divorced from the society in which people are living. It is the society at large, the way the economy works, and one’s family that encourages or even requires (to be successful) some of these characteristics/behaviors while discouraging others. In capitalism, some of the basest characteristics—such as competitiveness, individualism, greed—are encouraged and rewarded. This leads to putting the individual’s (and a corporation’s) best interests ahead of those of society.

- In order for a socially just and ecological society to function, educational efforts need to be taken to encourage compassion (instead of naked individualism), cooperation (instead of competitiveness), reciprocity and sharing (instead of greed and consumerism), an awe of nature in all its complexity and beauty (instead of thinking of nature mainly for its potential usefulness in producing commodities), and egalitarianism (instead of striving to get ahead of others). This means actively working to create a new ethic towards the land, the environment in general, toward our fellow human beings, our communities, and the other species with which we share this planet. The significantly greater time that people will have for purposes other than work will allow for more community activities, interactions with others outside the family and work, and to appreciate the natural world in all its complexity.

Closing Thoughts

I have outlined some of the main characteristics that I think are essential for an ecologically and socially humane and just economy and society. These are incompatible—in almost every way—with a capitalist economy. Doing away step by step with capitalism in a necessary long revolution will not automatically bring positive social or ecological change. That change will happen only if a large portion of the population believe in, and fight for, an environmentally sound and socially just society.

And it will take a huge shift in almost all of human activities, ways of thinking and behaving, including how we relate to each other and interact with the environment. New ethics will be needed for this new society to function. This is not an easy task, but what is the alternative? A system that, as it functions normally, destroys the very foundations of life through exploitation, waste, and greed is by definition an antiquated system. This is not an argument in favor of doing nothing in the here-and-now. We should be helping to stop the Keystone XL pipeline and encourage universities and other organizations to divest of holdings in fossil-fuel companies and fight for the environmental rights of poor communities. We can use these struggles in order to help educate others that, to solve the overall ecological crisis in all its ramifications, another system is necessary.

Is this an unattainable “utopia”? I think that, if it ever comes into being, an economy and society that is ecologically sound and socially just will have to embody most of the characteristics I have described above. There is no doubt that it will not happen in the near future. But I contend that it is no more utopian than to think that the financial and other strong business powers and their governmental representatives will allow you to make major changes to the financial system or the way international trade operates. What are the chances of, as some ecological economists have suggested, forcing banks to have very high (some have said 100 percent) reserves so they cannot create significant amount of debt or making major modifications in the workings of the World Bank and rules of the World Trade Organization so that they encourage equality and environmental justice? I think that those ideas are perhaps even more utopian than the possible creation of a new society. As the economist Joan Robinson once explained, “Any government which had both the power and the will to remedy the major defects of the capitalist system would have the will and the power to abolish it altogether.”8

It has been said, accurately in my opinion, that most people in this society can more easily imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. I fear that barbarism may be the fate that awaits our grandchildren and their children unless we can change that way of thinking and start to envision, and begin to work towards, an economy and society under truly democratic social control with the very purpose being to satisfy basic human needs, which as I have stressed many times, includes a healthy and thriving environment.

Notes

- On the growth imperative of capitalism see Chapter Three in Fred Magdoff and John Bellamy Foster,What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011).

- Hugo Lindgren, “If you were trying to name the greatest invention in human history it would be,”New York Times Magazine, June 7, 2013, http://nytimes.com.

- Leo Hickman, “Jeremy Grantham On How to Feed the World and Why He Invests in Oil,”GuardianEnvironment Blog, April 16, 2013, http://guardian.co.uk.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%,”Vanity Fair, May 2011, http://vanityfair.com.

- “Fourth Amendment,” http://law.cornell.edu.

- Laura Shin, “Using Fungi to Replace Styrofoam,”New York Times “Green” blog, April 13, 2009, http://green.blogs.nytimes.com.

- For information about ecological soil and crop management practices, see Fred Magdoff and Harold van Es,Building Soils for Better Crops, 3rd edition (Waldorf, MD: Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program, 2010). This book and others from the SARE program are free at http://sare.org/learning-center/books.

- Joan Robinson, “Review of R.F. Harrod,The Trade Cycle,”Economic Journal46, no. 184 (December 1936): 691–93.

No comments:

Post a Comment