Written by Richard Fidler and first published at Life on the Left Blog

The following is a slightly edited

text of a presentation I made to open a discussion on this topic at the Free

Transit Ottawa membership meeting March 6, 2019. It is now posted on FTO’s

Facebook page. – Richard Fidler

Climate

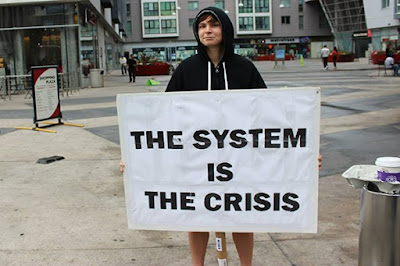

change is the most visible, most threatening expression of a larger, planetary ecological

crisis, the result of an economic system (capitalism) with an inherent growth

and profit dynamic which ensures that the exploitation of natural resources

(both renewable and non-renewable) exceeds the carrying capacity of nature. You

have read the almost-daily scientific reports, each more alarming than the ones

before, on the scope of the crisis. I won’t belabour the point.

Our approach

must be informed by, and congruent with, the challenge that crisis poses to the

way society must be organized if we are to halt and reverse the ecological

catastrophe toward which we are now hurtling.

The Trudeau government’s approach

At Paris in

2015, the prime minister pledged to limit Canada’s share of increased climate

warming to no more than 1.5 degrees. That translates into a 30% reduction in

greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) below 2005 levels. The First Ministers agreed

to this in 2016.

The federal policy is set out in what they call the Pan-Canadian Framework on Green Growth and Climate Change. It has “four main pillars: pricing carbon pollution; complementary measures to further reduce emissions across the economy; measures to adapt to the impacts of climate change and build resilience; and actions to accelerate innovation, support clean technology, and create jobs.”

Carbon pricing is the key “pillar” and it takes two forms:

1. A carbon

tax, gradually increased over time to encourage households and industries to

reduce carbon consumption. All revenues revert to the provinces, 90% going to

households. A levy on large industrial polluters took effect January 1, and one

on fossil fuels will begin in April, initially at $20 a tonne, to increase to

$50 a tonne in 2022. Major exemptions are provided for strategic industries,

including oil and gas, to protect “competitiveness.”

In fact, carbon taxes will always be limited to ensure that Canadian businesses are not disadvantaged by competitors’ prices and to avoid economic disruption that would motivate greater market intervention. But they are largely ineffective in reducing GHG emissions.

Both the UN Environment Program and the OECD have noted the inadequacy of Canada’s emissions reduction targets.

2. Carbon

offset schemes. Businesses invest in environmental projects around the world to

balance their own carbon footprints. These projects are usually based in

underdeveloped countries, and are designed to reduce future emissions through

introducing clean energy technologies or, for example, to offset pollution in

the North through promoting reforestation in the South.

An example is

“cap-and-trade.” The government sets a cap (limit) on the amount of GHG

emissions various industries can emit into the atmosphere. The limit is

gradually reduced over time to decrease total pollution levels.

That’s the

theory. What it amounts to is issuing permits to pollute, which can be traded

on carbon markets like stocks on the stock market. The market sets the price.

These schemes essentially give companies (with enough money) a right to

pollute, rather than forcing them to reduce pollution.

The system

makes pollution a commodity through credits and offsets that allow for

financial corporations to profit from polluting industries. Some provinces have

adopted similar plans.

Others are challenging carbon taxes in the courts. The

Ford government cancelled Ontario’s cap-and-trade program along with hundreds

of renewable energy projects (wind, solar, thermal) already under way.

The fundamental flaw

As James Wilt

noted in the Briarpatch article posted to our list,[1] carbon pricing doesn’t

regulate emissions, it just puts a price on them based on an arbitrary

calculation, the “social cost of carbon,” that tends to ignore the

“externalities” — the cumulative emissions, feedback loops, and

disproportionate impacts of climate change on countries in the Global South.

These are not encompassed in corporate cost-benefit analysis. For business,

they are just a cost of doing business.

Wilt

describes the carbon tax as “a deeply neoliberal and individualistic” approach

that “often excludes or minimizes impacts on fossil fuel corporations while

downloading moral and financial responsibility on households that burn fossil

fuels for transportation or heating. Perhaps most concerning of all is the way

it serves to create resentment for – and siphon energy from – far more

ambitious climate policy that would rapidly cut emissions, guarantee jobs, and

improve public services for all.”

However,

Canadian authorities, far from passively relying on market mechanisms, are

quite capable of aggressive action to implement their goals where these are

integral to their strategic profit and growth concerns. Missing from the

Pan-Canadian Framework is the other, more important component of the Trudeau

government’s climate approach: promoting further oil and gas exploitation and export,

especially through building pipeline and rail capacity. This endeavour totally

conflicts with its carbon-reduction promises.

In 2018

alone, the federal government announced $19 billion in new investments in dirty

oil.[2] $4.5 billion went to the purchase of the Trans Mountain pipeline. (The

Parliamentary budget director says the government paid one billion too much.)

The new pipeline will triple the quantity of oil transported, at a cost to

taxpayers of $9.7 billion. Once operational, it will increase the number of

supertankers in the Vancouver harbour from 40 to 600 per year. As the owner of

this major pipeline, but also its regulatory authority, the government has

placed itself in a huge conflict-of-interest situation.[3]

Bill C-69,

now in the Senate, will abolish the National Energy Board (NEB), substitute the

Canadian Energy Regulator and establish a separate Impact Assessment Agency

with a priority to “foster sustainability.” But as the pipeline owner, Ottawa

has a fiduciary obligation to maximize future oil shipments and revenues,

accelerate approvals and construction, curtail protests from the public and

First Nations, and even counter judicial opposition from the B.C. government.

And that’s

not all. Last fall, Finance Minister Morneau announced $2.7 billion in support

for investments to encourage oil companies to invest and produce more. In

January, Trudeau announced $1.7 billion more in credit lines to the oil

industry. And Alberta, frustrated by the delays in the Trans Mountain project,

will lease 4,400 railway cars which it says will move up to 120,00 barrels of

oil per day by rail by 2020.

Trudeau has

of course come out in support of the $40 billion LNG Canada project in northern

British Columbia, the largest infrastructure project in Canadian history. LNG

Canada is a carbon hog, its construction and operation being incompatible with

the B.C. NDP government’s own carbon-reduction targets as well as Ottawa’s.

These

subsidies, in total, rule out any possibility of achieving the government’s

vaunted carbon reduction goals.

And then

there are costs of restoring the tar sands lands, estimated by Alberta’s oil

regulator at $260 billion.

Imagine if

these amounts had instead been invested in sustainable development and

renewable energies.

Since the last

election, in 2015, tar sands production has increased by 24%. In November 2018

the NEB forecasted that domestic oil production will grow by 58% and natural

gas production will grow by 29 percent between now and 2040. The forecast

assumes the feds will implement the carbon tax as planned and that new

pipelines will be built to accommodate rising production. Just days ago, the

NEB gave its go-ahead to Trans Mountain for the second time, pursuant to the

review dictated by the Federal Court of Appeal’s overturn of its initial

approval last August.

The

government itself acknowledges the failure of its approaches. In a report

issued in December the federal department of Environment and Climate Change

said the policies currently in place will deliver only three-quarters of the

emission reductions required to meet Canada’s Paris target. But the minister

Catherine McKenna maintains Canada is on track: she says she is counting on

investment in public transit and the adoption of new technologies such as the

electric car over the next 12 years to close the gap.

New technologies?

This is a

common hope, frequently encountered on the left as well. But it’s an illusion.

In an article previously circulated on our list, ecosocialist Ian Angus

exploded the myth that geoengineering, nuclear power, carbon storage and other

techno-fixes — all of them promoted by the US socialist magazine Jacobin — can

be viewed as solutions to climate change.[4]

By way of

comparison, a recent study by Robert Gross of the Imperial College of London

concludes that the average period required for the adoption of the four most

recent leading electrical production technologies — nuclear, gas turbines,

photovoltaic (solar) cells, and wind turbines —was 43 years. Adoption was

defined as being well established but not yet dominant.[5]

Which means

that if we want to avert catastrophic climate change by 2050, we are

essentially reduced to using existing technologies.

Putting aside

Canadian governments’ commitment to expanding reliance on fossil fuel

production and export, which is completely irrational in view of the scientific

evidence on the source and pace of climate change, the parallel reliance on

market mechanisms to compensate for emissions through carbon credits and

technologies (not to mention nuclear) is equally deficient. The central error

is the attempt to respond to the climate challenge without challenging the

sacred cow of growth and competition for profit of a capitalist system that is

85% reliant on fossil fuels.

Yet the core

plank of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is the belief that capitalist

growth can be fundamentally “green.”

This illusion

is now being challenged even in some unexpected places. Consider, for example,

this article in the Fall 2018 edition of Foreign Policy magazine, a prestigious

US publication that exists, as it proclaims, “to serve decision-makers in

business, finance and government.”[6]

The author,

Jason Hickel, argues that the absolute decoupling of GDP from resource use is

impossible on global scale. There are physical limits to how efficiently we can

use resources. Once those limits are reached, any economic growth drives

resource use back up.

“Preventing

that outcome will require a whole new paradigm. High taxes and technological

innovation will help, but they’re not going to be enough. The only realistic

shot humanity has at averting ecological collapse is to impose hard caps on

resource use…. Such caps, enforced by national governments or by international

treaties, could ensure that we do not extract more from the land and the seas

than the Earth can safely regenerate. We could also ditch GDP as an indicator

of economic success and adopt a more balanced measure like the genuine progress

indicator (GPI), which accounts for pollution and natural asset depletion.

Using GPI would help us maximize socially good outcomes while minimizing

ecologically bad ones.

“But there’s

no escaping the obvious conclusion. Ultimately, bringing our civilization back

within planetary boundaries is going to require that we liberate ourselves from

our dependence on economic growth—starting with rich nations.”

He continues:

“This might

sound scarier than it really is. Ending growth doesn’t mean shutting down

economic activity—it simply means that next year we can’t produce and consume

more than we are doing this year. It might also mean shrinking certain sectors

that are particularly damaging to our ecology and that are unnecessary for

human flourishing, such as advertising, commuting, and single-use products.”

Alternative approaches

This brings

us to alternative strategies and approaches to climate change. Here I think we

need to bear in mind three principles in articulating alternatives:

1. The

precautionary principle: There must be no deployment of possibly dangerous

technologies (e.g. geoengineering).

2. The

importance of differentiated responsibilities: The Global North bears primary

responsibility for climate crisis, and must contribute disproportionately to

efforts to remediate in the Global South, the primary victims. As well, we need

to incorporate “grey emissions” (resulting from production in the South for

things consumed in the North) in national scenarios. Neither of these

principles are present in the Paris Accord of 2015, on which Trudeau claims to

base his approach. And I would add a third principle:

3. Social justice.

Workers should not have to pay the costs of transitioning from a problem they

did not create, and of which they are victims. This means no loss of jobs,

income, social protection or labour rights.

In my opinion

it is misleading to think that converting all existing energy sources from

non-renewable to renewable sources — summed up in the slogan “100% renewable

energy by (say) 2050”— will procure the energy needed to maintain existing

activities, let alone more extensive ones. Eliminating use of non-renewable

energy sources necessitates a complex of immense efforts; fossil fuel accounts

for 85% of energy production today.

Furthermore, the transition itself is a source of supplementary emissions, that must be offset if the carbon budget is not to explode. (Think of the energy required in building electric-powered vehicles to replace the existing vehicle fleet, no matter how composed.)

Furthermore, the transition itself is a source of supplementary emissions, that must be offset if the carbon budget is not to explode. (Think of the energy required in building electric-powered vehicles to replace the existing vehicle fleet, no matter how composed.)

How are we to

offset these expanded energy needs? In a productivist system any gain in

efficiency is used to increase production. So we need to reduce global energy

consumption, that is, reduce productive and/or transport activities. This means

challenging the capitalist growth imperative.

Does this

mean de-growth? Some production or services should not degrow but be suppressed,

ASAP: coal facilities and mines, oil extraction, weapons production, the

advertising industry, glyphosate, pesticides, etc. But others should grow –

such as renewable energies, organic agriculture, and essential services

(education, health and culture).

Obvious

measures: Here are just a few of the options (you can add many more):

Rapidly phase

out oil, gas, and coal extraction and stop subsidizing fossil fuels

Develop a

massive program of public investment in solar, wind, thermal energy

Initiate a

massive green housing program focused on energy-efficient social housing for

low-income residents, and retrofit existing buildings with electric heat pumps,

efficient appliances, and added insulation

Fund public

transportation, including urban, rural, and intercity options; construct a

pan-Canadian network of electrified passenger and freight trains

Employ people

to clean up abandoned wells, tailings lakes, and mining waste to prepare land

for return to Indigenous peoples

Break with

agribusiness, promote ecological agriculture and work with farmers to reduce

agricultural emissions

End

production of useless and dangerous things (start with weapons!)

Localize

production to the maximum, fight planned obsolescence

Redistribute

wealth, refinance the public education and care sectors

Develop new

ecologically sound industries to employ workers displaced by suppression of

non-renewable resource exploitation – while maintaining incomes and social

benefits.

Financing – Major tax reforms, increased high marginal tax rates. And cut useless expenditures, beginning with all military not converted to a home defense militia.

Local action

– Yes, but also global measures. And go beyond capitalism. Draw on indigenous

buen vivir concepts. And build alliances, anticapitalist coalitions of workers,

unemployed homemakers, farmers, indigenous communities, racialized minorities,

students, youth, poor against the entrenched fossil oligarchy. Link

decarbonization with opposition to capitalist austerity.

In particular

industries, unions can develop plans for alternative climate-friendly

approaches.

A good example is the Canadian Union of Postal Workers campaign,

“Delivering Community Power.” Establish postal banking, create a renewable

energy postal fleet, make post offices solar-powered community hubs for ditigal

access, provide charging stations for electric vehicles, etc. Integrate letter

carrier services with support to enable the ageing and disabled to live

independently.[7]

Green New Deal

– The proposal by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), a Democrat in the US Congress

and member of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), sets out a series of

objectives that are quite radical incorporating many of the above demands,

albeit within a general framework of “green capitalism.” It has attracted

support in Canada. Avi Lewis, an author of the Leap Manifesto, describes it as

“the Leap Manifesto, with increased altitude and velocity.”

The DSA’s

Ecosocialist Working Group released a statement recently supporting the Green

New Deal “while recognizing that its resolutions are conversation starters –

not complete and adequate blueprints.” The Group proposes improvements such as

setting firm target dates (“Decarbonize the economy fully by 2030”), democratizing

control over major energy systems and resources, etc.[8]

Also, we need to center the working class in a just transition: Decommodify survival by guaranteeing living wages, healthcare, childcare, housing, food, water, energy, public transit etc.

Demilitarize,

decolonize and strive for a future of international solidarity and cooperation.

Ultimately, we need a different kind of government with the political will to lead, coordinate and consolidate the transition, a government based on the support and protagonism of the victims of climate change, not its perpetrators.

_______________________________

These

comments borrow heavily from many authors more informed than I am on this

topic. In particular, my thanks go to those listed in the footnotes, as well as

Daniel Tanuro and Michael Löwy. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions expressed

are mine and do not necessarily engage Free Transit Ottawa. – Richard Fidler

[1] James

Wilt, “The

leftist’s case against the carbon tax.”

[2] Gabriel

Ste-Marie, “Toute

la Chambre des communes carbure au pétrole.”

[3] Paul

McKay, “SNC-Lavalin

and Trans Mountain: Two sides of a counterfeit coin.”

[4] Ian

Angus, “Memo

to Jacobin: Ecomodernism is not ecosocialism.”

[5] Philippe

Gauthier, “La

(trop) lente diffusion des technologies énergétiques.”

[6] Jason

Hickel, “Why

Growth Can’t be Green.”